What I learned living, studying and working in Sevilla, Spain.

By Norah Hively

As my departure date draws near, my mind begins to create a vision of what my travel experience will be like. But only a fraction of these apparitions present the physical idea of what things will look like. The majority of what I envision comes from what I imagine my experience will feel like. I imagine the feeling of learning about a new place, what I’ll take away from the newfound knowledge and how I know I’ll grow from what’s ahead. I realize much of what I’m sensing is ahead is responsible to what I’ve learned already from seeing the world. So, this is the rundown of the personal lessons I picked up from travel so far.

Stick around till the end for a surprise :)

Living, Studying, Working

In January 2024, I began a semester studying abroad. It was my junior year of college and my first time leaving the US.

Located in Andalucía, the region stretching the southern tip of Spain, Sevilla was the city I chose as my temporary home. I dual-enrolled at my American abroad program’s school and an international university. Along with my studies, I also took up an internship with a small audiovisual production company where I reached out to people for casting calls and attended production shoots. On the weekends, I typically explored other countries and cities. But nothing compared to Sevilla.

When I think of Sevilla, I think of actually living. I think of sun. I think of the streets lined with orange trees reaching for a blue sky. I think of the most beautiful park in the city only five minutes from my apartment. On my second day in Sevilla, I stumbled upon it by accident on a walk around my neighborhood. I had no idea the iconic destination was so close by. Getting lost in Parque de María Luisa for hours was one of my favorite pastimes; it was unlike anything I had ever seen. During my first visit, I wandered for hours and my fascination for the place never faded.

Immediately, I chose María Luisa as my place of safety for my time abroad. It had this energy about it that was hard to match. Now, I recall walking along Plaza de Espana as the evening light fell over the sandy brown brick, turning the whole place gold. The sun sparkled against the colorful tiles and twinkled on the surface of the half-circle canal filled with people rowing back and forth in wooden barcas. Women dancing Flamenco and men singing and strumming the guitar. The sound echoing among the arches.

The Plaza was just the half of it. Endless paths, fountains, statues, trees and playful kittens made it so I was never bored. The whole place allowed for a personal reflection beyond the physical one staring back at me in the pool waters. It served as somewhere to write, reflect, calm down and just be present. María Luisa was a large part of my life in Sevilla.

From my studies, I learned more about Spanish culture than anything else.

My history of documentary teacher was a young, quiet and reserved graduate student. Through her I learned about what it’s like pursuing the arts in Spain.

My intercultural communication and leadership teacher, adorning an “I ❤️ New York” tattoo, led discussions around the differences he saw between American and Spanish cultural norms and communications. He mentioned things like the lack of personal space that people provide in public and the staring eyes like the ones I received when I chose shorts and everyone else wore winter coats when it was almost 70 degrees Fahrenheit (pro tip: Andalusians dress for the season not the weather).

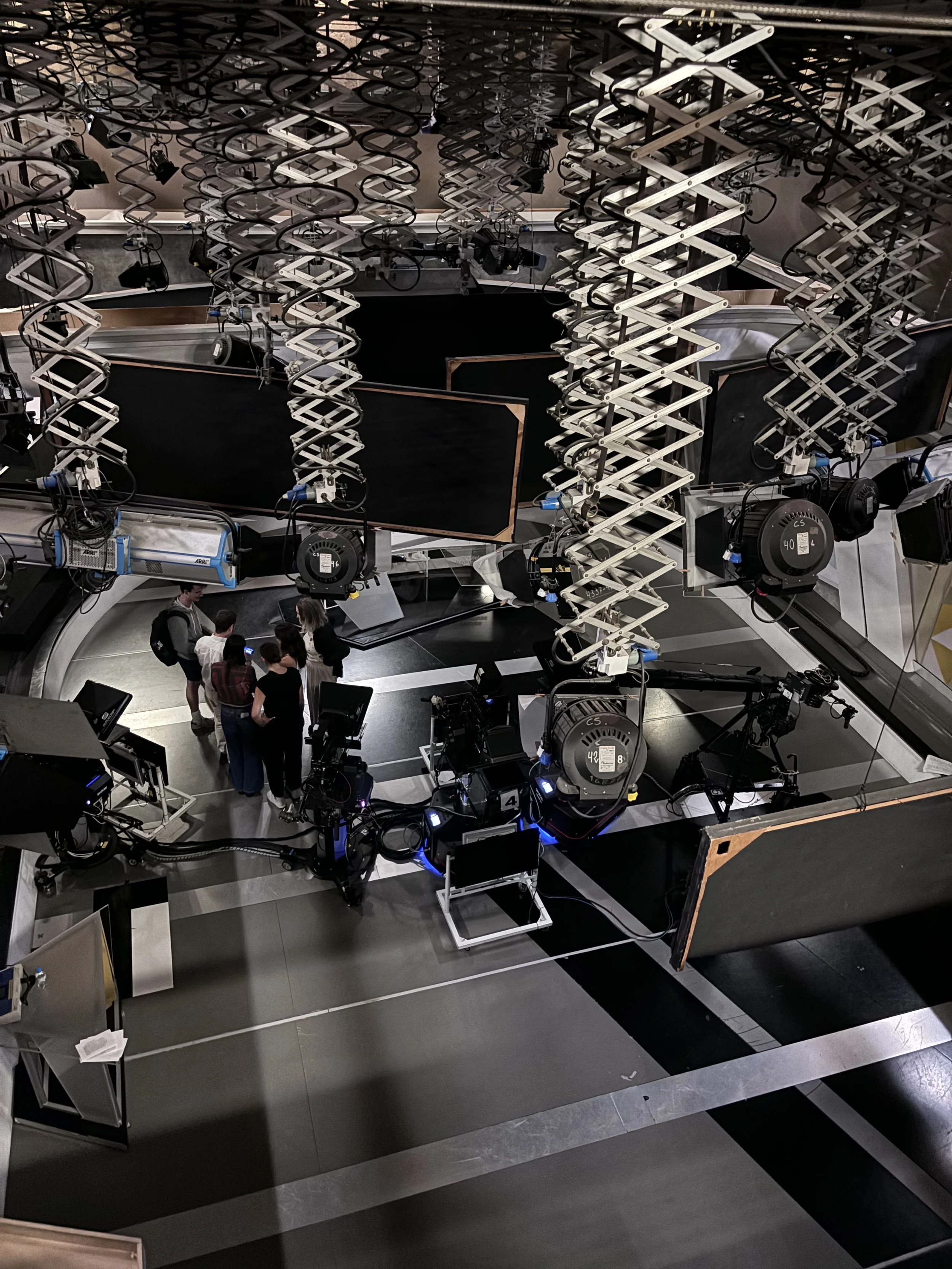

Another one of my professors was a news anchor. He took us to his news station where we got to see the newscast sets, the offices they worked in and the dressing rooms where anchors were having their makeup done.

Working in Sevilla was the most effective thing for learning about the culture. My boss had lived, studied and worked in Sevilla all her life. Cristina was younger yet she ran our office mostly by herself. Most days it was just her and I. The room was a small, long rectangle. Every thirty minutes or so she would take a break and roll up a cigarette, smoking it on the convenient balcony attached to the office. She worked anywhere from three to six hours a day. Every morning about an hour into working we went to breakfast. She paid me for my work with tostadas con tomate and cafes con leche. It was during these meals that I learned the most about Spanish culture.

Andalusian Culture

Cristina’s youthful, progressive nature taught me lots about the changes going on in her country and about the things that were being conserved, and, in her opinion, should be conserved as well as the things she believed were becoming outdated or seen as outdated by others. What I appreciated about her more political talks was that she told me all sides of the conflict. She told me why one side feels this way and one side feels that way.

One of the first things a Spanish teacher in my program taught us Americans when we arrived was that Spaniards were not “politically correct” he said holding up air quotes. In some ways, I found that to be true especially of southern Spain. But Cristina challenged that statement and, through her eyes, I was able to gain a fuller perspective of the place I was living.

An example of a challenging issue we discussed was the wealth gap in Sevilla which arose from us talking about the lack of A/C units in most buildings. During Sevilla summers, most people leave, if they have the means to. The average daily temperatures reach 110 degrees Fahrenheit and frequent heatwaves make those temperatures even hotter. If you aren’t wealthy, you likely don’t have an A/C unit. Most people don’t. Everyone stays inside despite Spaniards loving their outdoor time. It’s just too hot. Almost every building has a blackout grate that helps to block the light coming in but with no cooling it becomes a challenge to live daily life with no escape from the high heat.

Cristina possessed a deep appreciation for her city and traditions. Feria de Abril was her favorite of these traditions. Feria is a magical time of year in Sevilla. Feria de Abril directly translates to April Fair in English. Half of it resembles an American state fair besides everyone on rides with tuxes and Flamenco dresses.

The other half of the fair grounds are lined with colorful, striped tents or “casetas.” There are public and private casetas each having bars, tables and, most importantly, dancefloors or stages. In the street you are surrounded by string lights, music, food vendors and horsedrawn carriages. In the casetas, you spend night and day with friends and family dancing Flamenco and drinking rebujito, a dangerous but delicious cocktail made up of a mix of white wine and sparkling lemonade or lemon-lime soda with mint. It was through Cristina that I gained the lucky chance to experience a private caseta.

Unlike the public casetas, the private one was small, clean and intricately decorated. The women were in their finest Flamenco dresses so I stuck out like the outsider I was. But despite being outsiders, Cristina and her friends made my friend and I feel so very welcome.

I quickly found that Spaniards were extremely social people, you just have to find a way into their social circle. Everywhere I looked there were always people sitting at outdoor tables conversing over a cigarette, a cafe con leche or a beer. In between classes at the international university, people drank beers or espressos and smoked cigarettes between classes. At the end of a day of work or school, you went to meet your friends at a bar to do the same thing.

Andalusian vs. American Culture

From observing this and my day-to-day office life, I understood when Cristina said “we don’t live to work, we work to live.” This statement alone allowed me to understand most cultural differences I found between the US and Spain. In the US, we are the opposite. We spend our lives living for our work, for our job. In our society, we seem to be nothing without that. But with Spaniards it’s the opposite. Their families, friends and simple pleasures are at the forefront of their lives while work is simply what allows them to keep on living.

Getting to experience both these polar opposite cultures I believe has expanded my mind and what I want my life to look like so much. I admire Andalusians' view on life. It allowed me to question a lot of what I realized had been conditioned into me by my home country’s society. I always felt guilty prioritizing the things I enjoyed doing and being social over work or school. I had come to a point where it was extremely hard for me to be present and even understand my intention behind doing some things over others.

One more simple example was my commute to class and work: a 30-40 minute walk. Typically running late, I found myself speed walking to class often. What I came to realize was everyone walked extremely slow on their morning commutes, as if they had nowhere to be. Just strolling along. In southern Spain, people usually ran late but that was unacceptable where I came from. Me walking with a purpose, fast as possible, like my life depended on it, made heads turn. I would always be so anxious to get to a place even though, when I arrived late, it was never the end of the world like it would have been back home.

The Spanish seemed to have a complete opposing view of time and this mindset urged me to relax the longer I lived in Andalusia. I felt something opening slowly inside of me as if my peace were being restored. I had seen the value in taking things slower before but everything about university life in the US said this was wrong. Yet, here, everyone was putting it into practice and the world wasn’t falling down around them. Sipping a coffee slowly, sitting around over a beer with people after school or work, sunbathing on my building's rooftop—these were all things I recall having anxiety about doing at first; I always felt there was something else I should be doing.

Eventually, I relearned to enjoy these things. And I’m so glad I did because I more distinctly understand the importance of balancing both work and recreational time. I’ve learned to not feel so guilty about spending time the way I want to spend it.

This was good for my work as well. I didn’t lose any sense of drive when I came back to the US. If anything, my workflow and what I was working towards became clearer. As a result, what I needed to do to benefit my work also became more apparent because I wasn’t stressing as much during the time when I wasn’t working. Because that stress was constant, whether working or not working. And when you’re constantly stressed, it’s harder to chill out and do your work when it comes time to lock in. You’re clouded by all your self-critiques and shortcomings to the point where that’s all you think about and you eventually find yourself blind to all the strengths and genuinely good ideas you possess.

What I Learned Socially

When I left the US to go abroad, I was in a very bad place mentally, but I think this is what contributed to my experience being such a success. Hear me out.

I had gotten to a point where I felt so bad inside. Everyday felt like an endless loop of anxious turmoil. Not because I was leaving the country for the first time, in fact that was the last thing on my mind, but because a lot of things resurfaced in my personal life that I hadn’t dealt with yet. So, I barely thought or stressed about what was to come. My mindset was no matter if the program is bad, if I chose the wrong place, if I don’t make friends, none of it can make me feel lower than I do right now (it can only go up from here basically).

This way of thinking somehow helped me. I had a hunch that I needed a change, a drastic one. That was the only way to pull me out of the cycle. And beyond that, this way of thinking, at this point in life, made me completely unafraid to do what I was doing. I had almost no anxiety or fear about taking off. I found more comfort in it than anything. I had uncovered a sliver of optimism. A silver lining.

Retrospectively, my experiences and that opportunity couldn’t have come at a more perfect time in my life. Being at that state mentally while experiencing a new life and completely new things, made me see the benefits in doing the things I wanted. Living in a place where everything was new made it easier to not try to fit in to places I didn’t understand or that didn’t understand me.

I struggled pretty bad socially at first. Obviously, at the state of mind I was in, I felt pretty insecure on a day to day basis and meeting new people made that hard. By the third week, I was already planning weekend trips so that I wouldn’t feel so lonely. Nevertheless, I began to comprehend that it was hard for me to be with the people I was in closest quarters with: the other Americans. Living in a place with young people from multiple cultures allowed me to see and compare the differences between my country’s social norms and that of others’. I was surrounded by not only Americans, but also French, German and Spanish students.

Through Shannon, an American in my program, I met her class friends who were French. The six of us became super close. Shannon, just like me, also didn’t seem to understand the social norms of the other Americans. We both wanted to live. See new things, meet new people, dance all night and keep taking advantage of the opportunity we had living overseas. I didn’t want to live the same life as back home, I was tired of that. I didn’t want to Americanize my experience by attempting to make everything about my daily life exactly like my home life just somewhere else.

I was fascinated by the cultural differences, not critical, not judgmental. As I was in a new country and culture, I found it really hard and draining to be around others that didn’t share that same view; who thought themselves superior to something they didn’t even attempt to understand, yet, would flash the material elements of a place to show off to others back home. Not to say this was true of every American I came in contact with, but I found the people I first attempted to be friends with didn’t share the same values as me and that was more than alright. It allowed me to expand my scope.

Becoming best friends with four French people was beyond awesome in so many ways. Something I really appreciated in terms of group social dynamics was the directness we had towards one another. If we had an issue we typically hashed it out then and there. To outsiders, this may have looked more dramatic with the yelling (that often had playful undertones) or passionate body language, but in my eyes, what’s more dramatic than having a problem with someone or something they did and talking behind their back without attempting to hash things out?

Regular communication was also more direct than what I was used to back home which I appreciated. I understand now that this likely relates to my autism. I have always been more of a direct person, but I had done a lot of unlearning that over the years since being too direct can come across as rude in American society especially as a woman. Because of this candidness, I could be more myself with less social pressure to hold back and, consequently, I rediscovered how to be more myself in this way through our friendship. I learned so much from Ines, Theo, Tony, Antoine and Shannon. Finding people who loved me for me, in an unfamiliar place, at such a low point in my mental health healed me so very deeply. I miss them all everyday.

The Big Takeaway

Overall, the greatest, most beneficial takeaway from travel and living abroad was what it did for my mental health. Living the same cycle with which I became dissatisfied was limiting. Creating this major shift by removing myself from my current world and everything I knew allowed me to see the way I was living my life was not the only possible option for me. I was choosing to limit myself to the expectations of a society that didn’t serve me, that I didn’t find satisfaction in. When I returned back to the states, this mindset followed me and, you know what? People admired me for it. Maybe they wouldn’t always understand and would look at me like I was crazy, which before abroad would make me feel like I was doing something wrong, but now, by owning it, I can tell when I strike an interest by proposing an unorthodox perspective.

Existing on my own somewhere new, forced me to reflect on what I still needed serious work on internally. Despite having such an amazing experience and being beyond lucky, I still couldn’t escape the effects of my CPTSD. I was so mad at myself for not being able to fully enjoy all the gifts of beautiful places and people surrounding me. But, because of this, it became overwhelmingly apparent that no matter how perfect my external circumstances were, my internal landscape had to be dealt with and understood in order to get the most out of living. Having this experience made me braver and, subsequently, I became brave enough to face everything I needed to face when I went back to therapy in the US. Now, by helping myself, I’m beginning to understand how I can and want to move the world.

I am beyond grateful to have received the privilege of my life in Sevilla and traveling Europe. Travel truly is a privilege that, if you have access to, should never be wasted. In my mind, there aren’t many downsides to traveling long-term unless you see forcing yourself out of your comfort zone as a downside. But, what if being outside of your comfort zone is the greatest benefit—forcing you to grow and expand yourself? Almost anything you fear can become a learning experience when you approach it right. This is what travel taught me and it truly saved me. I’m so excited to take in even more of this beautiful world again soon.

Thanks for sticking around, here’s the surprise I promised:

First YouTube video ever!!!

Enjoy,

Norah <3